T’was ever thus

Dr Jo Sadgrove, USPG's Research and Learning Advisor

In my last blog post, I talked about the relevance of research work to organisations like USPG in enabling them to understand in detail the impact of the work that they are supporting around the world. By impact, I mean perhaps more importantly, the nature of that impact and its relationship to programme objectives – particularly where the outcomes from community level initiatives differ wildly from what was expected. The community life that USPG is supporting through partner churches across the vast gulfs in worldview, society, culture, storytelling and Christianity itself across the Anglican Communion, is so much more complicated and interesting than the stories and reports that are returned to London.

This is not a new problem for USPG. In our ongoing work on USPG’s archives, we are uncovering the tensions in the early life of the society (1700 – 1710) between the kinds of information that the organisation wanted to receive from missionaries, and the complexities of everyday life that missionaries were trying to negotiate in the American Colonies. The worldviews, community dynamics and challenges that missionaries encountered within the Colonies were not easily communicable back into the mindset of SPG in London.

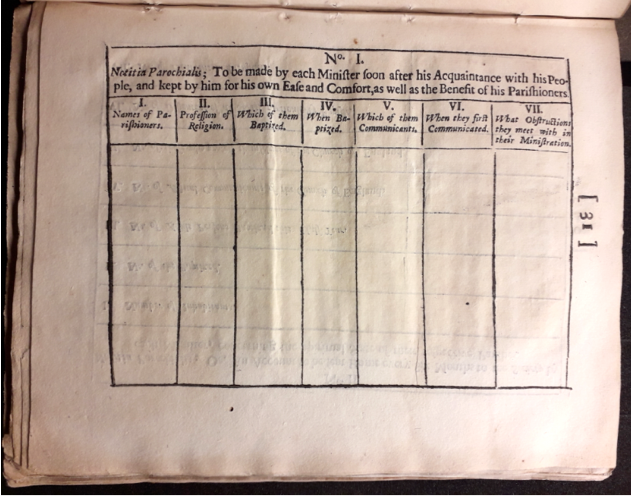

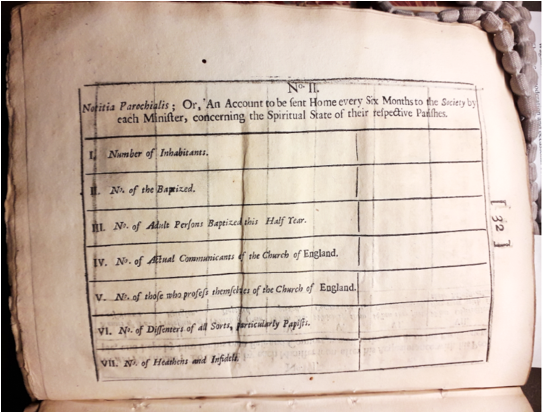

However ambitious and perhaps foolhardy it might seem now, SPG sought to recreate the structure of the English Parish in the contexts into which its missionaries were sent. Every 6 months, missionaries were required to fill out a form to be sent back to SPG in London detailing their progress in relation to this aim. The form ‘concerning the spiritual state’ of missionaries’ respective parishes records the number of inhabitants, of those baptized, of ‘communicants of the Church of England’, of dissenters and of ‘heathens and infidels’.

Examples of the reports produced in 1701 mentioned above

The reality of ‘life on the ground’ for missionaries in frontier societies that they themselves were learning how to navigate did not render the task of recording such information as straightforward as those in SPG London might have envisaged. Letters from the early archive indicate these challenges – for example that of Samuel Thomas, based in South Carolina, who struggles to account for the inhabitants of his parish using the categories that the SPG form requires. Or take the experience of Francis Le Jau, who, as a care giver in a context which is far more complex than a poor rural parish made up of white European settlers, is beset by anxieties as to the limits of his responsibilities. What might he do about those Europeans trading with indigenous groups, deliberately provoking war to create a market for their goods and to obtain slaves in return? What is his responsibility and the responsibility of SPG in this situation? What do the realities ‘on the ground’ mean for the project of establishing the parish system? Whose souls is he actually responsible for?

The structures of SPGs reporting requirements shape the letters and storytelling of missionaries in American colonies in the early 1700s. In a context in which decolonisation requires that all are able to tell their own stories on their own terms, accountability structures are yet another site with which USPG must engage. Perhaps more importantly, structuring the ways in which others can express their experiences undermines the ability of USPG to understand and share the distinctiveness of the storytelling traditions around the Communion, from which all could learn so much.